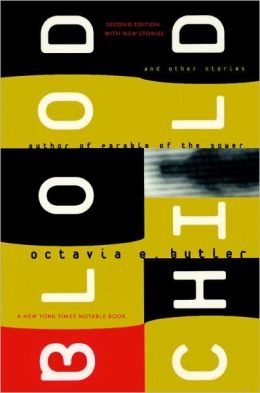

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. The past few columns in a row have talked about recent magazine issues, so I thought for this one we might do something different: look at an older collection, in this case Octavia Butler’s Bloodchild and Other Stories. The copy I have is the second edition (2005), which includes two stories that were not part of the original (1996) publication.

The initial five stories are “Bloodchild,” “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” “Near of Kin,” “Speech Sounds,” and “Crossover.” Then there are two essays, followed by two further stories, “Amnesty” and “The Book of Martha.” As Butler’s preface notes, she considers herself a novelist rather than a short story writer. These pieces are the exceptions to the rule, and they’re very much worth looking at. She also provides afterwords for each, interesting enough in their own right.

The first piece, “Bloodchild,” is fairly canonical—it’s the Butler short story I suspect most people will already have read. I’ve read it before more than once as part of classes in college, and it also regularly appears in anthologies; I think it serves as a “taster” example for the sort of concerns and issues Butler writes about. This isn’t surprising, either, because it’s a strong piece: the voice is compellingly on the edge of coming of age in a world radically different from ours with radically different needs and values; the imagery is disturbing and memorable; the alien-human relationship is complex and hard to sort into simple black-and-white morality.

The thing I found most interesting, on this re-read, was actually Butler’s afterword, in which she says: “It amazes me that some people have seen ‘Bloodchild’ as a story of slavery. It isn’t.” She notes that she sees it as a love story and a coming of age story and a pregnant man story, all angles that she approaches from a point of view that is ethically murky, emotionally complicated, and politically difficult. It reminds me of the power of her “Xenogenesis” saga, in that it’s also not easy to sort into a simple allegory with a moral point; I love that about Butler’s work, and wish I saw more of it in the field.

Second comes “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” an exploration of the implications of genetic diseases, treatments, and the leeway a person has to choose (or not) their life’s path based on biological factors. I found the science fictional elements intriguing—the ideas of the disease, DGD, and its pheromone sensitivity are well illustrated and integral to the emotional arc of the plot. The back-and-forth between the characters who are attempting to make some sort of life for themselves despite their disease is fascinating, particularly in the close, where Alan and the protagonist must deal with the implications of her special pheromones and what she can do for others. While she technically has a choice, it’s also not much of one; her biology, in some sense, is determinate of her future. It’s a rather bleak take on the effect of genetic influences, all things considered, but that also makes it a memorable read.

The next, “Near of Kin,” is a quick short about a college-age girl finding out, after her mother’s death, that her uncle is also actually her father. She’s fairly nonplussed by it, since she’d always loved him like a father anyway and her mother hadn’t been very much part of her life. It’s more of a character study than a story, but it’s a decent one of those. Butler’s afterword notes that the story was likely a result of thinking on all those Bible stories about sympathetic incest—an interesting angle to look back at the piece with, though it’s still rather brief and direct; not one of the strongest stories in the collection, certainly.

“Speech Sounds” is also a rather dark story dealing with disease, in a different direction than “The Evening and the Morning and the Night.” In this case, a stroke-like vector has affected the world’s population. Most have impaired cognitive functions and can no longer speak, or read, or write. The protagonist meets a man who is less impaired and might pair up with him but he’s murdered; then she rescues two children who can still talk, like her. The arc, as implied in that summary, is one of primarily loss but then a sudden turn toward meaning or purpose. It gives the story an interesting resonance, because to my mind it still seems to echo as mostly despairing with a faint ping of something more positive come possibly too-late. The afterword says that by the end Butler had rediscovered some of her faith in the human species, but it’s still a brutal and bleak future—whether or not these particular two children have speech, whether or not it might imply the disease has passed or just that they’re unique.

“Crossover” is another very-short piece, this one about a woman haunted by a man she lost and stuck in a dead-end life. (She also, potentially, might just be hallucinating.) I thought it read as more undeveloped or juvenile than those preceding it—feels a bit unfinished, like an idea that hasn’t quite grown all of the depth and nuance I’m used to in Butler’s stories. And, turns out in the afterword, it was a Clarion workshop story; so, it’s by far the oldest in the collection and is, in fact, from the very beginning of her career. It’s interesting for that, if nothing else, though it isn’t quite well rounded on its own. The imagery is strong, though.

The last two stories are additions to the second edition of the book, and they’re both from 2003. The first, “Amnesty,” is another story in the vein of the “Xenogenesis” books or “Bloodchild”—it’s about an alien people that have come to live on Earth in a complicated and ethically fraught relationship that might be coming closer to symbiotic with humanity. But it’s also about government overreach, and suspicion, and the danger people pose to one another; the afterword is very brief, and notes that the story was inspired by Doctor Wen Ho Lee’s treatment by the US government in the 1990s. As Noah informs the candidates to become translators and help the aliens learn about human culture, some of the worst things that happened to her were done by other people—not by the aliens. The emotional complexity of being a captive, being a colonized person, and being valuable at the same time is well represented here. It’s a dense story, and a moving one. I also appreciated the realism of the bleak economic and political situation, and how our protagonist chooses to make her way in that system, for better or worse. “Amnesty” is another good example of the kind of work people—me included, very much so—love Butler for.

Lastly, “The Book of Martha” is a thought experiment as much as it is a story. It follows a writer named Martha who god comes to—and asks her to make a change to humanity to help them survive their species’ adolescence. In the end, she decides dreams that give them the things they want while teaching them to grow up a little will be the best way, though not painless or free of mishap. I found this one a little duller than the rest, perhaps because it is a thought experiment: one long conversation between Martha and god about consequences and needs and humanity. It’s one way of looking at utopia, though—it has to be individual to each person.

Overall, Bloodchild and Other Stories is a strong read and a satisfying one that should do a good job of introducing readers to Butler’s work. Seven stories, two essays on writing; it’s a solid balance, and one that provides some interesting ideas to consider further.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.